Large-scale cloud applications are usually built using interconnected services that can be rather hard to troubleshoot. When a service is scaled, simple logging doesn’t cut it anymore and a more in-depth view into system’s flow is required. That’s where distributed tracing comes into play; it allows developers and SREs to get a detailed view of a request as it travels through the system of services. With distributed tracing you can:

OpenTracing is an open standard describing how distributed tracing works.

There are a few key terms used in tracing:

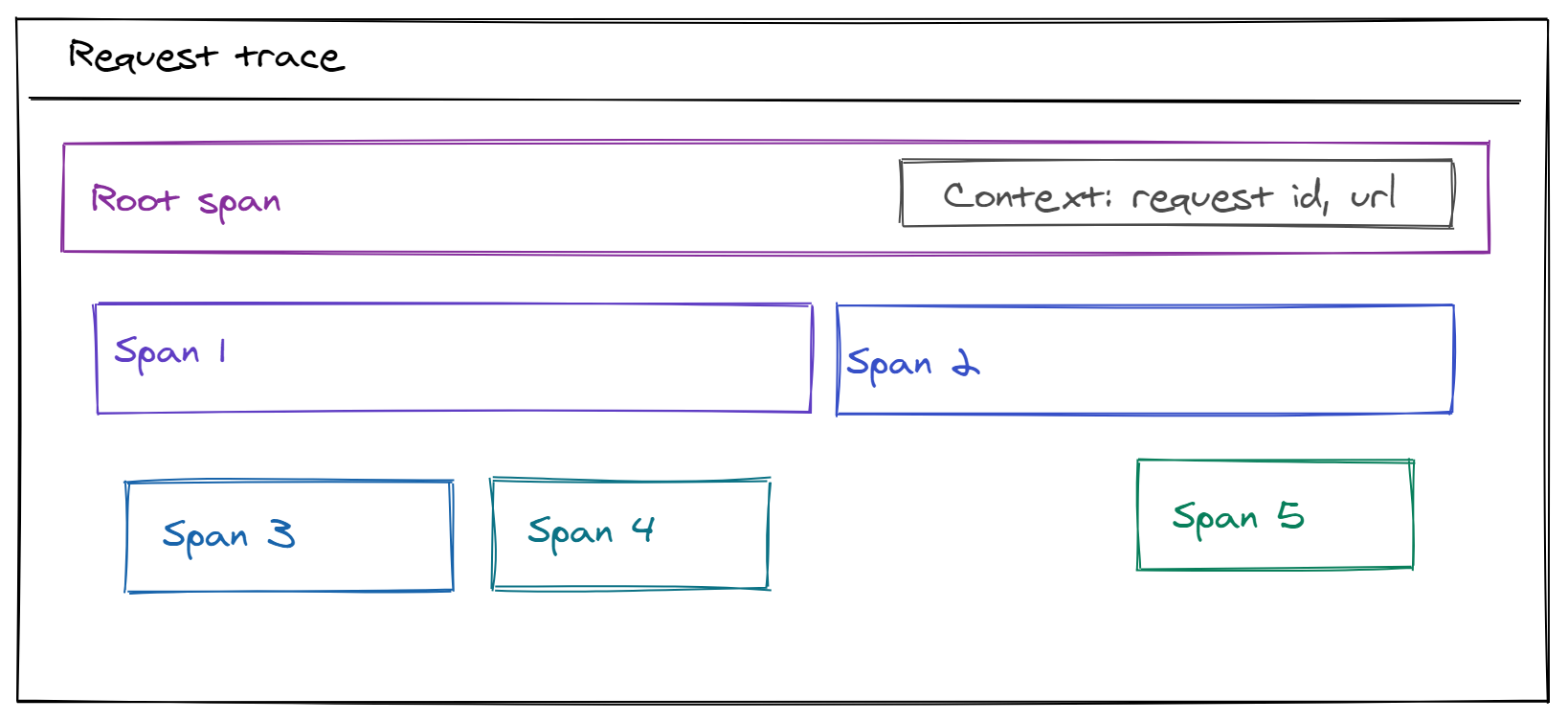

A trace recording usually looks something like this:

We’ve previously explored an OpenTracing implementation in the first post of this series. Next, we want to add distributed tracing capabilities to mattermost-server. For this, we’ve picked OpenTracing Go.

In this article we’ll discuss all the nitty-gritty details of implementing a tracing system in your Go application without littering your code with repetitive, boilerplate tracing code.

So what are we actually working on? We want to make sure that every API request that’s being handled by our server will get recorded into a trace, together with context information. This gives us the ability to dive deep into the execution and allow easy problem analysis.

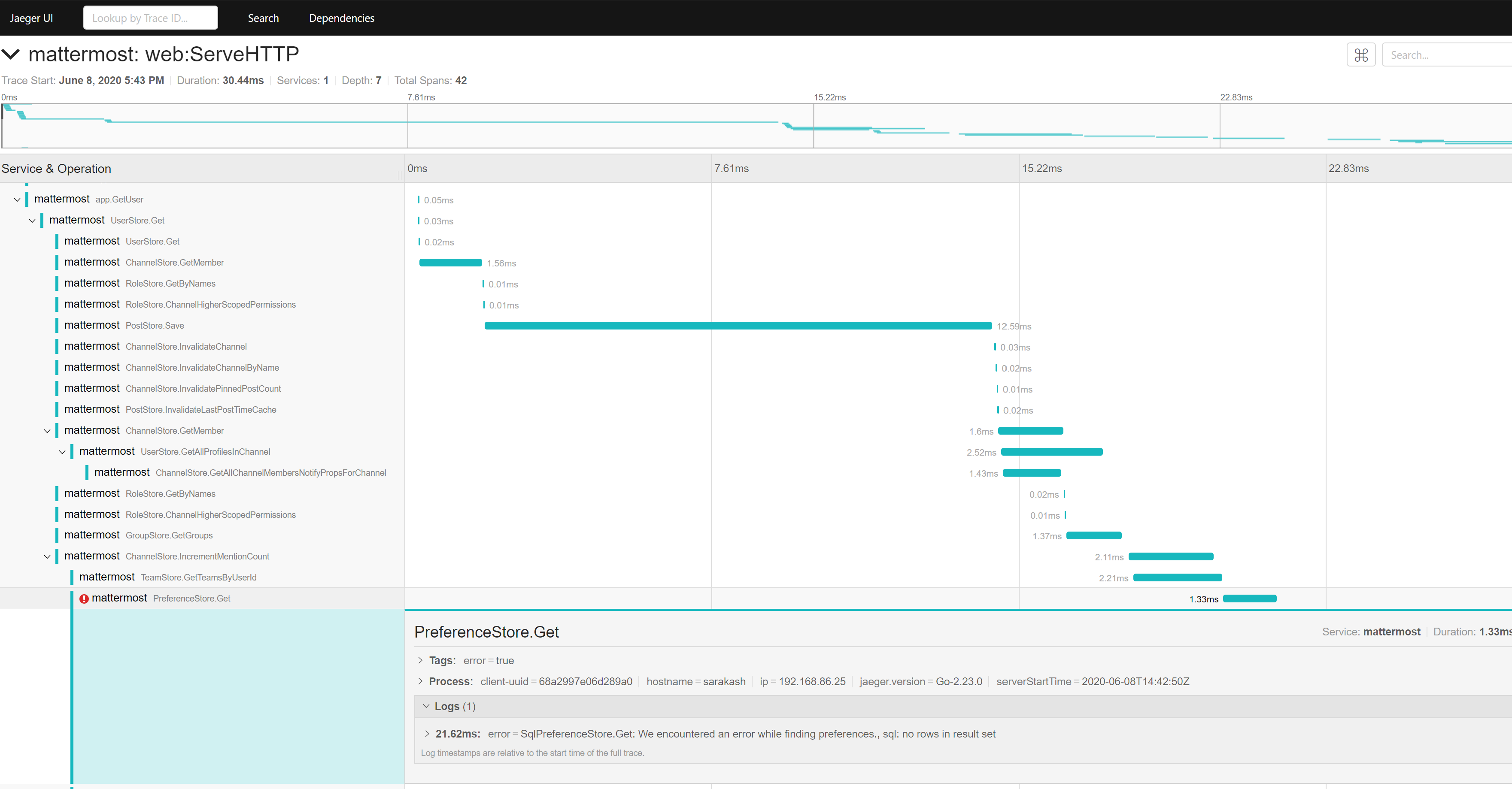

The resulting system trace will look like this (using Jaeger web-ui visualization):

To add tracing to any API call, we can do the following in our ServeHTTP function:

package web

import (

// ...

"github.com/opentracing/opentracing-go"

"github.com/opentracing/opentracing-go/ext"

spanlog "github.com/opentracing/opentracing-go/log"

)

func (h Handler) ServeHTTP(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

c := &Context{}

// Start root span

span, ctx := tracing.StartRootSpanByContext(context.Background(), "apiHandler")

// Populate different span fields based on request headers

carrier := opentracing.HTTPHeadersCarrier(r.Header)

_ = opentracing.GlobalTracer().Inject(span.Context(), opentracing.HTTPHeaders, carrier)

ext.HTTPMethod.Set(span, r.Method)

ext.HTTPUrl.Set(span, c.App.Path())

ext.PeerAddress.Set(span, c.App.IpAddress())

span.SetTag("request_id", c.App.RequestId())

span.SetTag("user_agent", c.App.UserAgent())

// On handler exit, do the following:

defer func() {

// In case of an error, add it to the trace

if c.Err != nil {

span.LogFields(spanlog.Error(c.Err))

ext.HTTPStatusCode.Set(span, uint16(c.Err.StatusCode))

ext.Error.Set(span, true)

}

// Finish the span

span.Finish()

}()

// Set current context to the one we got from root span - it will be passed down to actual API handlers

c.App.SetContext(ctx)

// ...

// Execute the actual API handler

h.HandleFunc(c, w, r)

}

Next, we’ll modify the actual business logic function that’s called by the API handler to nest it inside the parent span (we’ll use SearchUsers as an example):

func (a *App) SearchUsers(props *model.UserSearch, options *model.UserSearchOptions) ([]*model.User, *model.AppError) {

// Save previous context

origCtx := a.ctx

// Generate new span, nested inside the parent span

span, newCtx := tracing.StartSpanWithParentByContext(a.ctx, "app.SearchUsers")

// Set new context

a.ctx = newCtx

// Log some parameters

span.SetTag("searchProps", props)

// On function exit, restore context and finish the span

defer func() {

a.ctx = origCtx

span.Finish()

}()

// ...

// Perform actual work

// ...

// In case of an error, add it to the span

if err != nil {

span.LogFields(spanlog.Error(err))

ext.Error.Set(span, true)

}

// Return results

}

Rather straightforward, right? We marked our “entry-point” by creating a root span, populated it with useful context information, passed the context down the stack, and created a new span underneath it.

We could stop right here, because this is all you need to have a working trace! But for a large application like mattermost-server wrapping all of the 900+ API handlers in tracing code would be incredibly labor intensive and will create a lot of noise in the source code.

So, can we do better?

Before diving into our solution, I want to first introduce the decorator pattern.

To quote Wikipedia:

In object-oriented programming, the decorator pattern is a design pattern that allows behavior to be added to an individual object, dynamically, without affecting the behavior of other objects from the same class. The decorator pattern is often useful for adhering to the Single Responsibility Principle, as it allows functionality to be divided between classes with unique areas of concern. The decorator pattern is structurally nearly identical to the chain of responsibility pattern, the difference being that in a chain of responsibility, exactly one of the classes handles the request, while for the decorator, all classes handle the request.

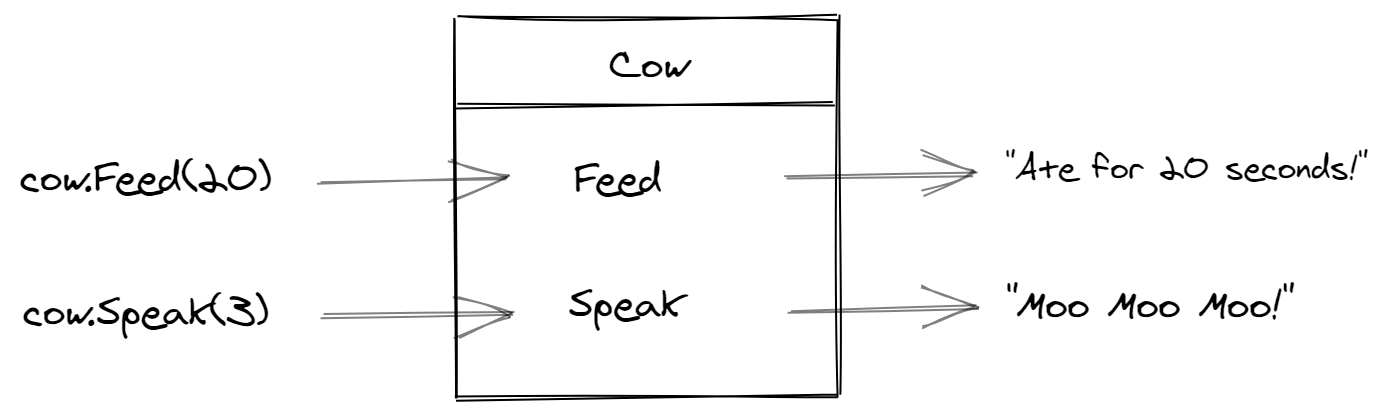

In simpler terms, let’s say we have an object called Cow that has some methods:

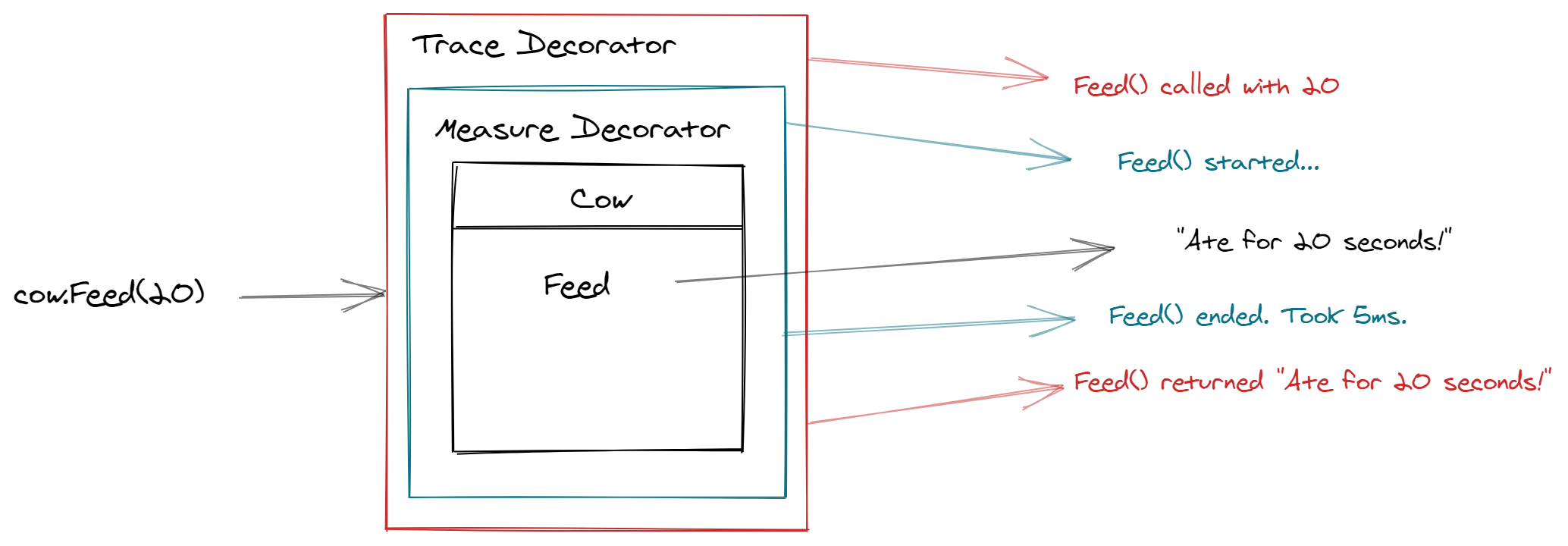

We want to introduce additional functionality on top of what Cow already does, without modifying the actual code of the Cow object. For example, we want to measure performance of each method and log the parameters that are being passed to each method. Here’s how it would look if we apply the decorator pattern:

We wrapped each method of Cow in a chain of additional functions: f(x) = y became f(x) = a(b(y)), with each function having its own responsibility.

If we apply the same pattern to our problem, we can decorate all of mattermost-server API calls with OpenTracing, without actually modifying the functions themselves!

Implementing such functionality in other, dynamic, languages is rather trivial. For example, here’s how JavaScript handles it given a simple Cow object:

const cow = {

feed: function(x) {

return `Ate for ${x} seconds!`

},

speak: function(x) {

return `${"Moo ".repeat(x)}!`

}

}

console.log(cow.feed(20))

console.log(cow.speak(3))

We can wrap it in a proxy:

const tracerHandler = {

get: function(target, prop, receiver) {

if (typeof target[prop] === "function") {

return function(...args) {

console.log(`'${prop} 'called with arguments: `, ...arguments);

return target[prop](...arguments);

};

}

}

};

const timerHandler = {

get: function(target, prop, receiver) {

if (typeof target[prop] === "function") {

return function(...args) {

console.log(`starting '${prop}'`);

const t1 = window.performance.now();

const res = target[prop](...arguments);

const t2 = window.performance.now();

console.log(`'${prop}' took ${t2 - t1}ns`);

return res;

};

}

}

};

const proxy = new Proxy(cow, tracerHandler);

const proxy2 = new Proxy(proxy, timerHandler);

console.log(proxy2.feed(20));

console.log(proxy2.speak(3));

Unfortunately, in Go, there’s no way to do this in a performant manner, and the regular approach would involve using reflection which can seriously impact performance on the underlying code.

The implementation of the decorator pattern we chose involved three parts:

Quoting Go FAQ

Although Go has types and methods and allows an object-oriented style of programming, there is no type hierarchy. The concept of “interface” in Go provides a different approach that we believe is easy to use and in some ways more general. There are also ways to embed types in other types to provide something analogous but not identical to subclassing.

type Animal struct{

Name string

}

type Cow struct{

Animal

}

func (c Cow) Speak() {

fmt.Printf("Moo, I am a %s", c.Animal.Name)

}

func main() {

a := Animal{Name:"Cow"}

c := Cow{Animal:a}

c.Speak()

}

How does struct embedding help us in the implementation of a decorator pattern?

type Speaker interface {

Speak(x int)

}

type Animal struct {

Name string

}

type TraceAnimal struct {

Speaker

}

type MeasureAnimal struct {

Speaker

}

func (c Animal ) Speak(x int) {

fmt.Println(strings.Repeat("I am a " + c.Name + " ",x))

}

func (c TraceAnimal) Speak(x int) {

fmt.Printf("Running Speak(x) function with x=%d!\n",x)

c.Speaker.Speak(x)

}

func (c MeasureAnimal) Speak(x int) {

fmt.Println("Timing Speak() function...")

t := time.Now()

c.Speaker.Speak(x)

fmt.Printf("Speak(%d) took %s\n", x, time.Since(t))

}

func main() {

a := Animal{Name: "Cow"}

c := TraceAnimal {Speaker: a}

d := MeasureAnimal{Speaker: c}

d.Speak(2)

}

Running the following code will yield:

Timing Speak() function...

Running Speak(x) function with x=2!

I am a Cow I am a Cow

Speak(2) took 0s

So we’ve basically implemented two decorators over the original Speak() method. First we started timing the execution in MeasureAnimal, then passed it to TraceAnimal, which in turn called the actual Speak() implementation.

``

This works great and stays performant since we don’t use any dynamic techniques such as reflection. However this is very verbose and requires us to write a lot of wrapper code - and that’s no fun at all.

We can do better!

Using the methods we’ve discussed in parts 1 and 2 of this series we can scan the interface of the struct we want to wrap and collect all the information needed to generate the decorators/wrappers automatically. Let’s dig in.

First of all, we kick off the AST parser on our input file that contains the interface and start walking through the found nodes:

package main

import (

"bytes"

"flag"

"fmt"

"go/ast"

"go/parser"

"go/token"

"io/ioutil"

"log"

"os"

"path"

"strings"

"text/template"

"golang.org/x/tools/imports"

)

func main() {

fset := token.NewFileSet() // Positions are relative to fset

file, err := os.Open("animal.go")

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("Unable to open %s file: %w", inputFile, err)

}

defer file.Close()

src, err := ioutil.ReadAll(file)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

f, err := parser.ParseFile(fset, "animal.go", src, parser.AllErrors|parser.ParseComments)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

ast.Inspect(f, func(n ast.Node) bool {

// ... Handle the found nodes

})

}

To differentiate interface methods from other AST nodes, we can do the following:

ast.Inspect(f, func(n ast.Node) bool {

switch x := n.(type) {

case *ast.TypeSpec:

if x.Name.Name == "Speaker" {

for _, method := range x.Type.(*ast.InterfaceType).Methods.List {

methodName := method.Names[0].Name

// Here we can parse all the required information about the method

methods[methodName] = extractMethodMetadata(method, src)

}

}

}

return true

})

Let’s define a couple of structs to help us collect information about methods:

type methodParam struct {

Name string

Type string

}

type methodData struct {

Params []methodParam

Results []string

}

// For each found method we'll store its name, params with their types, and return types in methods := map[string]methodData {}

Now let’s write a short function to populate these structs with metadata about a method:

func formatNode(src []byte, node ast.Expr) string {

return string(src[node.Pos()-1 : node.End()-1])

}

func extractMethodMetadata(method *ast.Field, src []byte) methodData {

params := []methodParam{}

results := []string{}

e := method.Type.(*ast.FuncType)

if e.Params != nil {

for _, param := range e.Params.List {

for _, paramName := range param.Names {

paramType := formatNode(src, param.Type)

params = append(params, methodParam{Name: paramName.Name, Type: paramType})

}

}

}

if e.Results != nil {

for _, r := range e.Results.List {

typeStr := formatNode(src, r.Type)

if len(r.Names) > 0 {

for _, k := range r.Names {

results = append(results, fmt.Sprintf("%s %s", k.Name, typeStr))

}

} else {

results = append(results, typeStr)

}

}

}

return methodData{Params: params, Results: results}

}

Now we can run the parser on our interface and we’ll get something like: map[Speak:{Params:[{Name:x Type:int}] Results:[]}].

As you can see, we collected all the information needed about interface methods and we can now move on to generating the decorator with this data.

Let’s get to it! We’ll start by defining a few helper functions that will be useful during code generation. They will operate on the metadata we’ve collected before.

helperFuncs := template.FuncMap{

"joinResults": func(results []string) string {

return strings.Join(results, ", ")

},

"joinResultsForSignature": func(results []string) string {

return fmt.Sprintf("(%s)", strings.Join(results, ", "))

},

"joinParams": func(params []methodParam) string {

paramsNames := []string{}

for _, param := range params {

s := param.Name

if strings.HasPrefix(param.Type, "...") {

s += "..."

}

paramsNames = append(paramsNames, s)

}

return strings.Join(paramsNames, ", ")

},

"joinParamsWithType": func(params []methodParam) string {

paramsWithType := []string{}

for _, param := range params {

paramsWithType = append(paramsWithType, fmt.Sprintf("%s %s", param.Name, param.Type))

}

return strings.Join(paramsWithType, ", ")

},

}

Next we’ll create a Go Template for both our decorators:

|

|

I know it looks a little scary, but the premise is rather simple. Given the following metadata: map[Speak:{Params:[{Name:x Type:int}] Results:[]}] we want to generate a new struct that embeds our Animal and wraps its calls in additional functionality.

I’ll go through the template line by line:

$element.Params using the helper functions defined aboveFor the Timer decorator, we’ll write the following template:

|

|

This is very similar to the template above, only this time we record the start time of the function and print the elapsed time on exit.

With these templates in hand, we can now generate the decorators!

// Create output buffer

out := bytes.NewBufferString("")

// Parse the template and pass it the helper functions

t := template.Must(template.New("my.go.tmpl").Funcs(helperFuncs).Parse(tracerTemplate))

// Execute the template and pass it the metadata we collected before

t.Execute(out, metadata)

// Add needed imports and format the code before printing

formattedCode, err := imports.Process("animal_tracer.go", out.Bytes(), &imports.Options{Comments: true})

if err != nil {

fmt.Printf("cannot format source code, might be an error in template: %s\n", err)

return err

}

// print it out!

fmt.Println(string(formattedCode))

The result will be:

package animals

import "fmt"

type AnimalTracer struct {

Speaker

}

func (a *AnimalTracer) Speak(x int) {

fmt.Printf("Running Speak(x) with 'x'=%v ", x)

a.Speaker.Speak(x)

}

Beautiful!

Similarly, running the generator over the timerTemplate will yield:

package animals

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

type AnimalTimer struct {

Speaker

}

func (a *AnimalTimer) Speak(x int) {

fmt.Println("Timing Speak function...")

__t := time.Now()

a.Speaker.Speak(x)

fmt.Printf("Speak took %s\n", x, time.Since(__t))

}

Using the techniques from the previous section, we can now generate the OpenTracing decorator we want by using the following template:

{{range $index, $element := .Methods}}

func (a *{{$.Name}}) {{$index}}({{$element.Params | joinParamsWithType}}) {{$element.Results | joinResultsForSignature}} {

origCtx := a.ctx

span, newCtx := tracing.StartSpanWithParentByContext(a.ctx, "app.{{$index}}")

a.ctx = newCtx

a.app.Srv().Store.SetContext(newCtx)

defer func() {

a.app.Srv().Store.SetContext(origCtx)

a.ctx = origCtx

}()

{{range $paramIdx, $param := $element.Params}}

{{ shouldTrace $element.ParamsToTrace $param.Name }}

{{end}}

defer span.Finish()

{{- if $element.Results | len | eq 0}}

a.app.{{$index}}({{$element.Params | joinParams}})

{{else}}

{{$element.Results | genResultsVars}} := a.app.{{$index}}({{$element.Params | joinParams}})

{{if $element.Results | errorPresent}}

if {{$element.Results | errorVar}} != nil {

span.LogFields(spanlog.Error({{$element.Results | errorVar}}))

ext.Error.Set(span, true)

}

{{end}}

return {{$element.Results | genResultsVars -}}

{{end}}}

{{end}}

Phew, this was quite a trip, huh? I hope you found it interesting. You can see the actual generator implementation inside mattermost-server in /server/channels/app/layer_generators/main.go.

Side note: This is just one way of handling this problem. Not everyone wants to rely on using code-generation too much since it hides a lot of implementation and complicates the build process (you have to re-run the generators each time your interface changes). We’ve settled on this approach due to its flexibility and performance.

If you have any notes or ideas on how this could be implemented in a cleaner way - please stop by the Mattermost Community server - I’ll be very glad to discuss it further.